Focusing on the Little Picture:

Imagine that you’ve just bought a large canvas to paint a landscape on. You have a little bit of knowledge when it comes to painting, but like me, maybe you’re still a bit of a novice. You start by painting a basic sky, then you work on a nice-looking tree. After you get this done, you look up at the clock, and you realize you’ve already labored for over an hour. Then you look back down at the canvas in front of you, and ninety percent of it looks back at you, completely empty. Immediately, the thought of filling up the rest of the canvas seems a bit overwhelming. So you put down the brush, intending to come back to it later in the day. But you never do, because you’re not quite sure how to finish the piece. This same scenario has happened to me- albeit, it was a digital painting that I left incomplete. Yet, the same principle applies.

My point- I would love to be able to complete large-scale pieces of art eventually. But at the moment, I’ve found that trying to create large-scale pieces of art is probably not a good idea because the work involved is a bit too overwhelming. The exception to this might be if I’m following a tutorial. But if I’m trying to create a large piece of art from imagination or even reference, it’s just not a good use of my time. Simply put, I’m still a novice, so I don’t quite know what I’m doing yet. And for that reason, my goal right now is to focus on creating small pieces of art that I’m confident I can finish. And if you’re just getting started as an artist, I might recommend that you try the same.

Smaller is Timelier:

There are two main reasons that I find focusing my time on small projects to be a best practice. For starters, the smaller the piece, the quicker you can get to the finish. I should probably use the term “quicker” lightly. In this case, even if you start out as an artist by sketching single flowers on a small sketch pad, this may end up taking longer than you think. Whenever you’re learning a new skill, you’re going to be inherently slower or more methodical compared to someone that been at the skill for a while. As an example, someone who only bakes cookies every once in a while will probably find themselves constantly looking back at the ingredients list, carefully measuring the ingredients, and so on (I’m kind of guilty of this). It may take them thirty minutes just to get the dough ready. In comparison, a full-time baker with several years of experience can seem to throw all the ingredients in a pot and have the dough ready instantly. They know what they’re doing, so they don’t find the need to slow down or double-check themselves constantly as they go.

None of this is to say that it’s going to take you an hour to create a simple sketch like the one I mentioned above. However, it could take you twenty to thirty minutes to do it, while a more experienced artist might manage it in five or ten. Now apply this logic to large-scale pieces of art. For a beginner, it could take them hours and hours to finish a huge landscape painting. Yet a professional might finish it in only an hour or so. All of this is one reason I say to start small. When you’re new to art, it’s just going to take an extra bit of time to get things done because you’re learning in the process. And you don’t want to frustrate yourself by working for hours on a large project but feeling like you’re not making much progress. Instead, start small to make it accomplishable. As you do more and more, you’ll get faster, and you might find large-scale pieces more time-effective.

Smaller is Easier:

Another big reason to focus on small projects when you’re just beginning is the amount of detail that’s required. Here’s one way to think about it. If you were to draw a huge picture of a dog with an intent on realism, the larger the picture, the more detail that is required. If it’s a large close-up, you would have to draw a lot of individual hairs to achieve a sense of realistic fur. If you didn’t add all these details, the blank space between the eyes, mouth, and nose might make the finished piece look like line art. In comparison, if you were to draw the dog on a much smaller scale, you’re inherently going to be much more limited on the details that you can add, as well as that are needed to achieve a level of realism. (Think about distant trees versus one that’s a stone’s throw away.)

In effect, you reduce the level of detail that is needed to create a realistic result, which in turn, should make the piece much easier to accomplish. You’ll still probably be learning some things that you’ll need to know to work on a larger, more detailed portrait, but you’ll be starting from a simpler place. This means that the amount of errors you can make is inherently smaller. Plus, if you do make an error when you’re working on something small scale, it should be a lot easier to correct. Or, if you feel that you can’t correct it, it’s still going to feel much less stressful moving your pencil a few inches over on the sketchpad page to try again compared to pulling out a new ultra-sized canvas.

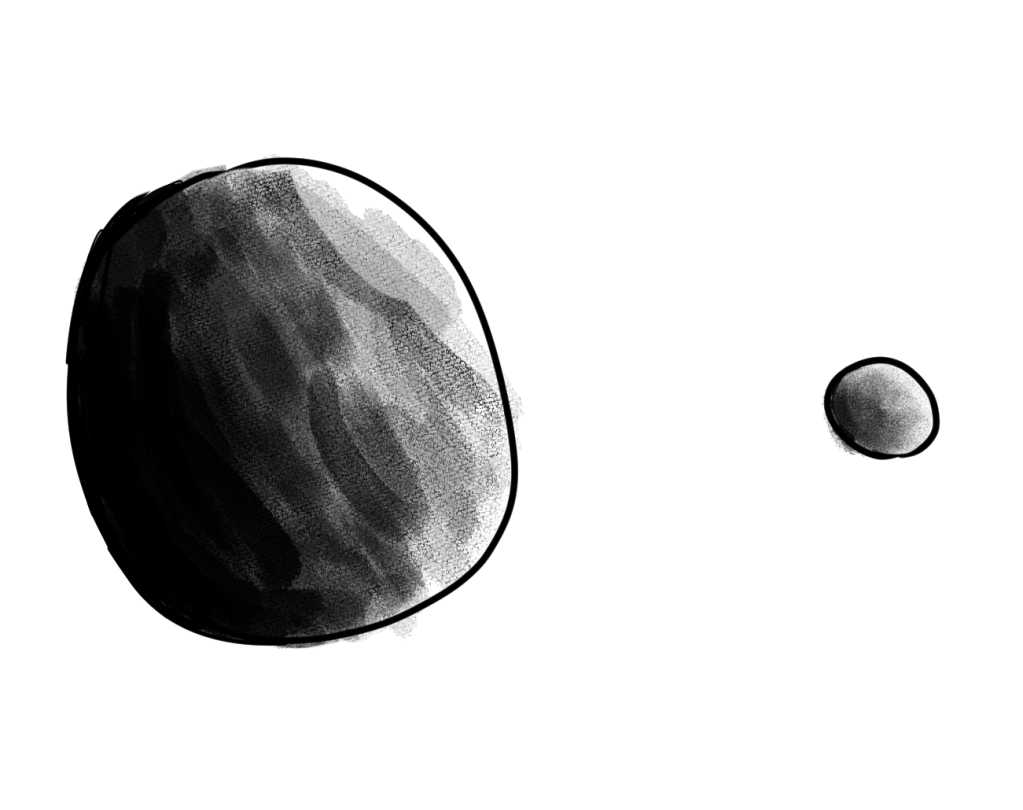

Errors aside, you’ll still be learning a lot by focusing on small-scale art. In the case of sketching a dog, you still may find yourself sketching individual hairs to create a realistic sketch. But it’ll be on a much smaller, easier scale. As an example, whereas a large portrait might require ten lines for a clump of hair, a small sketch might achieve a realistic effect with one or two. The same principle goes for inanimate objects. When sketching a small house, you may only have to sketch a few lines to indicate a realistic grain on the siding, yet, for a much larger sketch you may have to double or triple your work to achieve the best level of detail. A similar benefit comes with shading. When you’re shading small scale, there is inherently less room to spread out a shading gradient. The darks and the lights are going to be inherently closer to each other, which may make the transition areas easier to shade because you aren’t having to spread it out over a large area.

(As seen in the above image, the smaller sphere has a gradient over a much smaller area, which makes it a bit easier to figure out the transitions. In comparison, the larger sphere would require a bit more fine tuning to create a crisp shading gradient. As an example, if you were to recreate this with a pencil, you would have to pay more attention to the amount of pressure you’re applying to create a smooth shading gradient over the larger area.)

Go Small, But Not too Small!

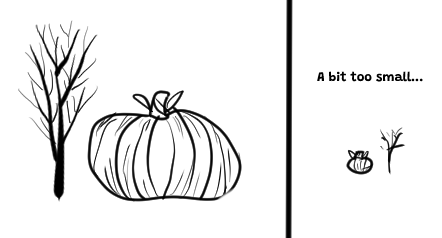

While I think there are some great benefits to learning art through small-scale projects, I would also warn against going too small. When I first tried creating small-scale landscapes, I limited myself to about a two-by-two-inch block in a sketchpad. For a very rough outline of deciding where I might want to put things in, this might’ve been okay. For actually sketching a landscape, however, it was far from ideal. Simply put, this area was too small for me to add any meaningful detail. A tree could have just as easily been a twig poking out of the ground because there wasn’t enough space to make it look like a tree. To sketch a landscape on small-scale with meaningful detail, I probably should’ve gone for an area around the size of a postcard, which is about four by six inches. With this, I could’ve made small details to indicate the leaves or bark on trees, which would’ve helped prepare for me future, larger projects.

(The “too small side”: Is it an apple, a bag, or pumpkin? Is it a stick, a tree, or an exploding firework?)

That being said, there’s no concrete rule to follow on picking the size for a small-scale piece of art. If you wanted to sketch a single flower without the stem, a two-by-two-inch block could be sufficient to allow the addition of specific details. Furthermore, some things can be drawn super-small simply because they don’t require the same level of detail as a realistic sketch. A simple, two-by-two-inch cartoon sketch of a puppy could require the same level of detail as a cartoon sketch of a puppy in a ten-by-ten-inch format. However, the smaller sketch should be easier because you won’t have to draw long lines. And if you’ve been drawing for any length of time, you know the longer the line you have to draw to connect two points, the more room you leave for your hand to swerve off course. If you start small though, you can train your hands to be steady and build yourself up to creating the larger pieces of art.

Final Thoughts:

Instead of pressing yourself to fill up an entire canvas or a large piece of paper, try going smaller on your next piece of art. In short, you’ll be putting a lot less pressure on yourself, and it should be easier to get to the finished result while still learning some of what you’ll need to create larger pieces later. That being said, really think about size before you get started. You’ll want to make sure you won’t go so small that you can’t add any details, or go so big that you’re overwhelmed as to the amount of detail you need to add. And, as always, have fun with it. As I said before, I’m still a novice myself, so none of this is a must-to guide on learning to create art. So if you find yourself bored when creating art small scale, go for that larger scale. But if you’re currently finding yourself struggling to finish a piece or overwhelmed at the prospect of starting one, try going small, and see how it goes.

Leave a comment